https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/en/2022/06/civil-defence-book-the-war-in-peoples-heads/

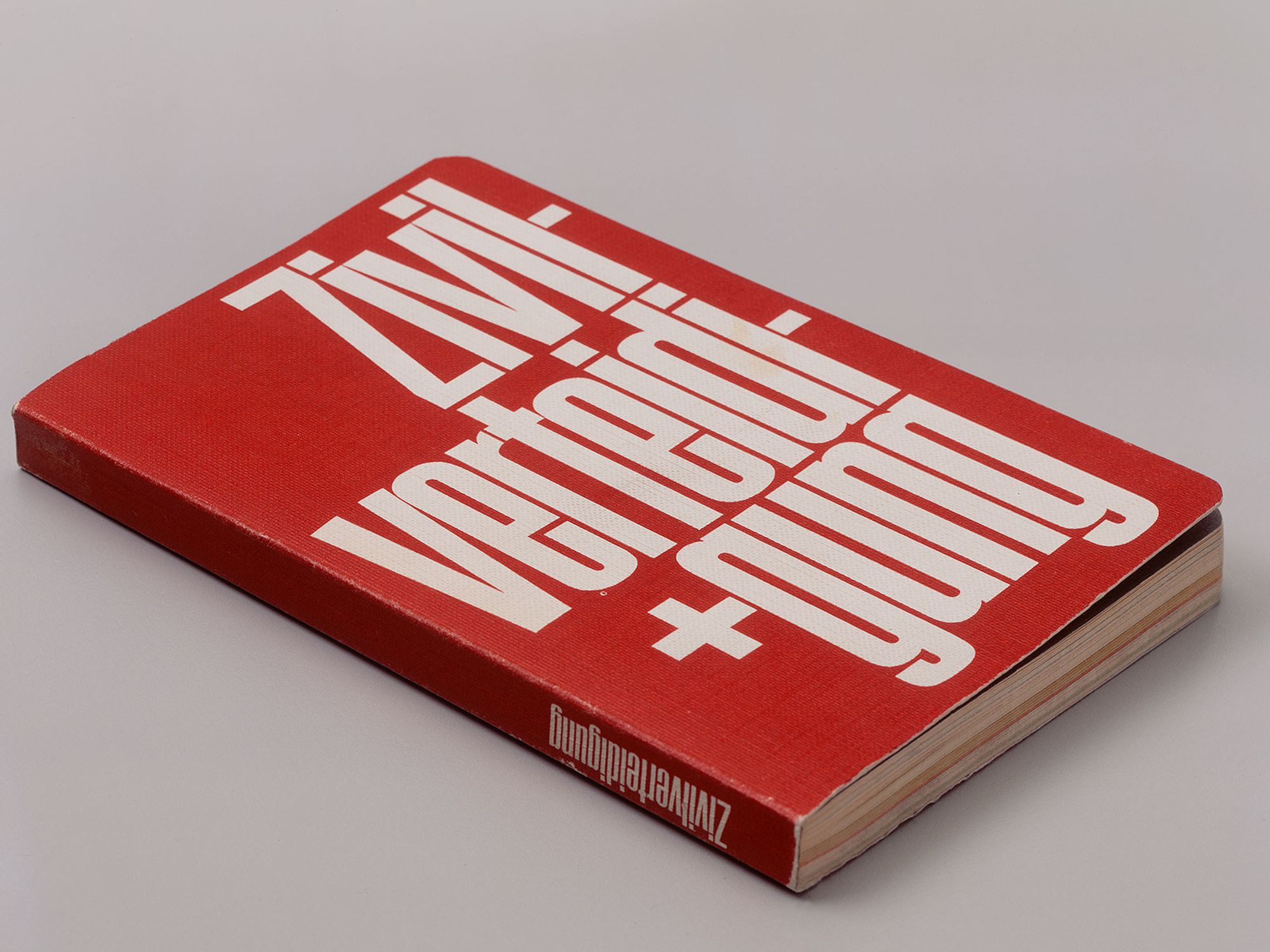

In autumn 1969, a special kind of mailshot landed in every household in Switzerland. «The Zivilverteidigungsbuch» – a 320-page paperback book with an eye-catching red cover, it was printed in a run of 2.6 million copies, in all three national languages. The total cost of the controversial work came to 4.8 million Swiss francs. Both the book and the controversy surrounding it provide a glimpse of Switzerland’s mental state during the Cold War years.The book was sent out by the head of the Federal Department of Justice and Police, CVP-affiliated Federal Councillor Ludwig von Moos (1910-1990). In the letter accompanying this delivery to the nation’s people, he explained the purpose of the work as follows: “The booklet is intended as a guide: in relation to future events, to trials that could beset our population, natural catastrophes and major disasters; it is also in preparation for times of potential danger to our homeland… Keep the booklet in a safe place, read it carefully, check every once in a while that everything is prepared, and do your bit to make sure we can look to the future with confidence.”In terms of style and format, the book was based on the Soldatenbuch, a manual for Swiss Army soldiers published in 1958, and was written in the style of a guidebook for pathfinder technology. Even today, a flick through its pages will make you shudder. Natural disasters are not the main focus; instead, the booklet’s content is almost exclusively about war in our country. The booklet was intended to prepare the civilian population for armed conflict and nuclear war. It described the course of a war from preparation to a nuclear strike, to guerrilla warfare and liberation. The scenario was based, essentially, on World War II. The Zivilverteidigungsbuch gave the public to believe that Switzerland was poised and ready to handle a nuclear strike: “When nuclear weapons are used, the impact decreases the further you get from the blast site. We must work on the assumption that everything in the core zone of the explosion will be destroyed. In a zone further out, however, where everything above ground has also been destroyed, the civilian population will have survived in the shelters.”The work also became controversial because of the concept of the enemy that it presented: the enemy came from within as much as from without. The book painted a picture of a Switzerland that had been infiltrated by foreign ideas, by parties and organisations from abroad. Its collaborationist warnings clearly referred to the Swiss Left. In the Zivilverteidigungsbuch this is referred to as the second form of war: “The second form of war is so dangerous because it is not outwardly recognised as war. The war is concealed, obscured. It plays out against the backdrop of an outward appearance of peace, and takes the form of a civil revolution. The beginnings are small and apparently innocent – the end is as grim as the war itself.” The illustrations also deserve a mention. Firstly, factual infographics were used, but then there were also sketchy illustrations; people without recognisable faces were rendered as shadowy lines and shaded red in the relevant passages.The production of the book was coordinated by two men, working with a group of other authors – there were no women among them: military intelligence officer Albert Bachmann (1929-2011), and historian Georges Grosjean (1921-2002). Bachmann was a colonel in the General Staff of the Swiss Armed Forces and was described as an “extraordinarily dazzling and colourful character, afflicted with certain adventurous traits”. In the late 1970s he assigned the amateurish spy Kurt Schilling to spy on the Austrian armed forces, and later tried to set up a clandestine resistance organisation. In 1979 he was forced to take early retirement. The Zivilverteidigungsbuch received a very critical reception in Switzerland, and sparked debate within the Federal Council even before it was published. The liberal Federal Councillor Hans Schaffner (1908-2004), head of the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, is said to have repeatedly pressed for a more objective representation. In parliament, there were a number of attempts on the issue. “Ultimately, the defensive tenor of the project wasn’t a good fit with the prevailing mood of the political and cultural turning point in the 1960s”, the Federal Archives now note.Understandably, there was great outrage in left-wing circles, as these groups were defamed in the booklet as potential public enemies. A number of bookshops offered to exchange the free book for current books by Swiss authors, free of charge. The work was even publicly burned at a demonstration in front of the federal parliament building. The controversy was particularly intense at the Schweizer Schriftsteller Verband (SSV), the Swiss writers’ association, as SSV member Maurice Zermatten had provided the French translation of the Zivilverteidigungsbuch. In response, the Olten Group split off from the writers’ association; the group would go on to become an important voice. The Olten Group members included, among others, Peter Bichsel, Anne Cuneo, Walter Matthias Diggelmann, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Max Frisch, Vahé Godel, Ludwig Hohl, Kurt Marti, Mani Matter, Adolf Muschg, Walter Vogt and Otto F. Walter. The Olten Group only disbanded in 2002.The Zivilverteidgungsbuch was an unsuccessful project, implemented at the wrong time. The high costs probably also had something to do with the long production time, of five years. The booklet was devised at the beginning of the 1960s, and by the time it finally appeared in 1969, the zeitgeist had changed: Switzerland wanted to come out of the shadow of spiritual defence, the Geistige Landesverteidigung, and turn its attentions to something new. The publication of the Zivilverteidigungsbuch was also followed abroad. The book was reprinted in a number of countries and appeared in Arabic, Chinese and Japanese, sometimes even featuring the Swiss cross.

1969年秋天,一份特殊的邮件寄到了瑞士的每个家庭。《瑞士民防手册》是一本320页的平装书,封面醒目地印有红色,以瑞士的三种官方语言印刷了260万份。这本备受争议的作品总成本达到了480万瑞士法郎。这本书和围绕它的争议反映了瑞士在冷战年代的心理状态。

这本书是由联邦司法和警察部长、瑞士人民党成员的联邦委员路德维希·冯·莫斯(Ludwig von Moos,1910-1990)发出的。在附带给全国人民的信中,他解释了这本作品的目的:“这本小册子旨在作为指南:帮助我们的人民应对未来可能发生的事件、可能困扰我们人民的审判、自然灾害和重大灾难;它也是为了准备潜在的危险时刻……请将这本小册子放在安全的地方,仔细阅读,定期检查一切是否准备就绪,并为我们能够充满信心地展望未来做出您的贡献。”

就风格和格式而言,这本书以1958年出版的《瑞士士兵手册》为基础,采用了路径导航技术指南的风格。即使在今天,翻阅这本书的页面也会让人不寒而栗。自然灾害并不是主要关注点;取而代之,这本书几乎完全关注我们国家的战争。

这本书旨在为平民人口准备武装冲突和核战争。它描述了一场战争的全过程,从准备到核打击,再到游击战和解放。这个场景主要基于第二次世界大战。

《瑞士民防手册》让公众相信瑞士已经做好准备应对核打击:“当使用核武器时,冲击范围随着距离爆炸现场的增加而减小。我们必须假设在爆炸核心区域的一切都将被摧毁。然而,在更远的区域,地上的一切也被摧毁,平民人口将在掩体中幸存下来。”

这本书的争议也源于它所呈现的敌人概念:敌人既来自内部也来自外部。这本书描绘了一个被外国思想、党派和组织渗透的瑞士。它的合作警告明显指向瑞士左派。在《瑞士民防手册》中,这被称为第二种形式的战争:“第二种形式的战争非常危险,因为它并不被公开认为是战争。战争是隐藏的,被掩盖的。它在和平外表的背景下展开,采取的形式是内战。起初看似微小无害,但最终会变得像战争本身一样残酷。”这本书中的插图也值得一提。首先,使用了事实信息图,但还包括了手绘插图;在相关段落中,没有可辨认的面孔的人被描绘成模糊的线条,并用红色进行阴影处理。

这本书的制作由两位男性协调完成,他们与其他作者一起工作,其中没有女性:军事情报官阿尔伯特·巴赫曼(Albert Bachmann,1929-2011)和历史学家乔治·格罗让(Georges Grosjean,1921-2002)。

巴赫曼是瑞士武装部队总参谋部的上校,被描述为“一个非常引人注目和多才多艺的人,具有一些冒险特质”。在20世纪70年代末,他曾派遣业余间谍库尔特·席林(Kurt Schilling)监视奥地利武装部队,后来还试图建立一个秘密抵抗组织。1979年,他被迫提前退休。

《瑞士民防手册》在瑞士引起了非常大的争议,并在出版之前就在联邦委员会内引发了辩论。自由党联邦委员汉斯·沙夫纳(Hans Schaffner,1908-2004)曾多次要求更客观地呈现内容。在议会中,也有一些关于这个问题的尝试。联邦档案现在指出:“最终,该项目的防御性倾向与20世纪60年代政治和文化转折的普遍气氛不符。”

可以理解的是,左翼圈子对此非常愤慨,因为这些群体在小册子中被诬蔑为潜在的公共敌人。一些书店提供免费将这本书换成瑞士作家的现代作品。这本书甚至在联邦议会大楼前的一次示威活动中公开焚烧。争议在瑞士作家协会(Schweizer Schriftsteller Verband,SSV)中尤为激烈,因为SSV成员莫里斯·泽尔马滕(Maurice Zermatten)提供了《瑞士民防手册》的法语翻译。作为回应,奥尔滕团体(Olten Group)从作家协会分离出来,并成为一个重要的声音。奥尔滕团体的成员包括彼得·毕赫塞尔(Peter Bichsel)、安妮·库内奥(Anne Cuneo)、瓦尔特·马蒂亚斯·迪格尔曼(Walter Matthias Diggelmann)、弗里德里希·迪伦马特(Friedrich Dürrenmatt)、马克斯·弗里希(Max Frisch)、瓦埃·戈德尔(Vahé Godel)、路德维希·霍尔(Ludwig Hohl)、库尔特·马蒂(Kurt Marti)、马尼·马特(Mani Matter)、阿道夫·穆斯赫(Adolf Muschg)、瓦尔特·福格特(Walter Vogt)和奥托·W·瓦尔特(Otto F. Walter)等人。奥尔滕团体直到2002年才解散。

《瑞士民防手册》是一个在错误的时机实施的失败项目。高昂的成本可能也与制作时间长达五年有关。这本小册子最初设计于20世纪60年代初,直到1969年才最终出版,而当时的时代精神已经发生了变化:瑞士希望摆脱精神防御的阴影,转向新的事物。《瑞士民防手册》的出版也引起了国外的关注。这本书在许多国家重新印刷,并以阿拉伯语、中文和日语等多种语言出版,有时甚至带有瑞士国旗。